Checking the numbers means more than checking just the numbers

Reader Jody A. didn't like what she saw in this Zero Hedge post. I think the site is fun to read and often makes good points in very provocative ways but this post is careless. Here are some points to ponder:

- The quantitative part of their argument relies on Tom Friedman's Law of Statistics (explained here); that the extreme case of some lower-income person exploiting every angle is used to represent the average such person.

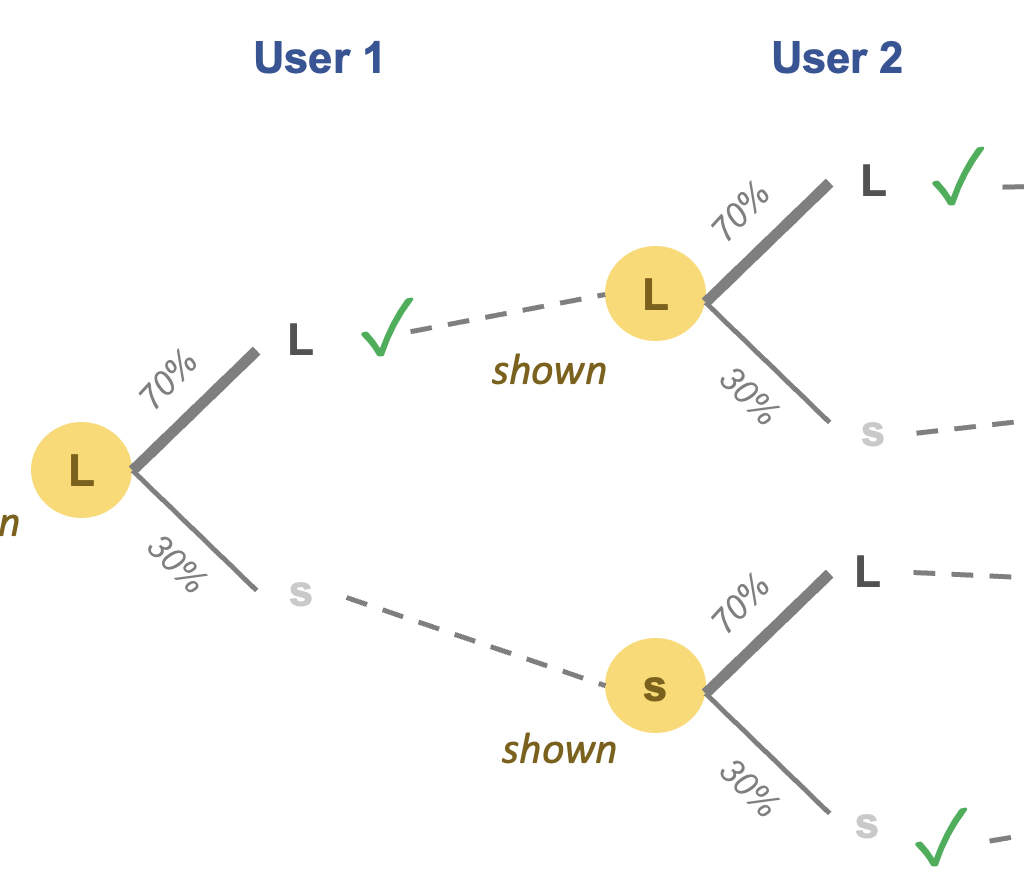

- Assuming that a group of dishonest people exists who exploit every angle to get government money, it is hard to imagine that this group constitutes all, if even most, of the low-income people who receive government aid. If there are different types of poor people, they should be analyzed as separate groups. This is the central idea behind Chapter 3 of Numbers Rule Your World.

- The ideological basis of their argument makes no sense to me. If we concede that the middle-income person would end up with less disposable income than the lower-income person, then we'd expect that the middle-income people will take lower-paying jobs so as to increase their disposable income. But I have not seen reports of such reverse social mobility. Theory needs to fit reality. This hole in the theory needs to be covered.

- An implicit assumption of this argument is that people choose to be poor, or that people are given incentives to choose to be poor. The implication is that poverty is a problem of misconstrued incentives. This suggests that poor people would not exist if we had the right incentives in place. This suggests we live in Lake Wobegon where everyone is above average.

- It is often useful to think about the relative scale of numbers. The US poverty rate (living at or under minimum wage) was 14% in 2009, equalling 44 million persons (see here). The proposed tax cut to the super-wealthy (top 1%) is valued at $36 billion next year (using the numbers here). This amount is sufficient to pay $820 to every person living under minimum wage.

We are often faced with quantitative claims like this. Of course, we wish to "check the numbers". Checking the numbers means more than checking the computation. I have checked various other things here: whether the observed result is properly generalized to the population for which the claim is made; whether like is compared to like; what the underlying theory is, and whether it makes sense; how the underlying theory can be reality-checked, in both its assumptions and its implications; and how to put the numbers into perspective.