Exercising fails to stop obesity, doh

Kaiser Fung (Numbersense, Principal Analytics Prep) reacts to an article claiming more gym memberships have not reduced obesity rate.

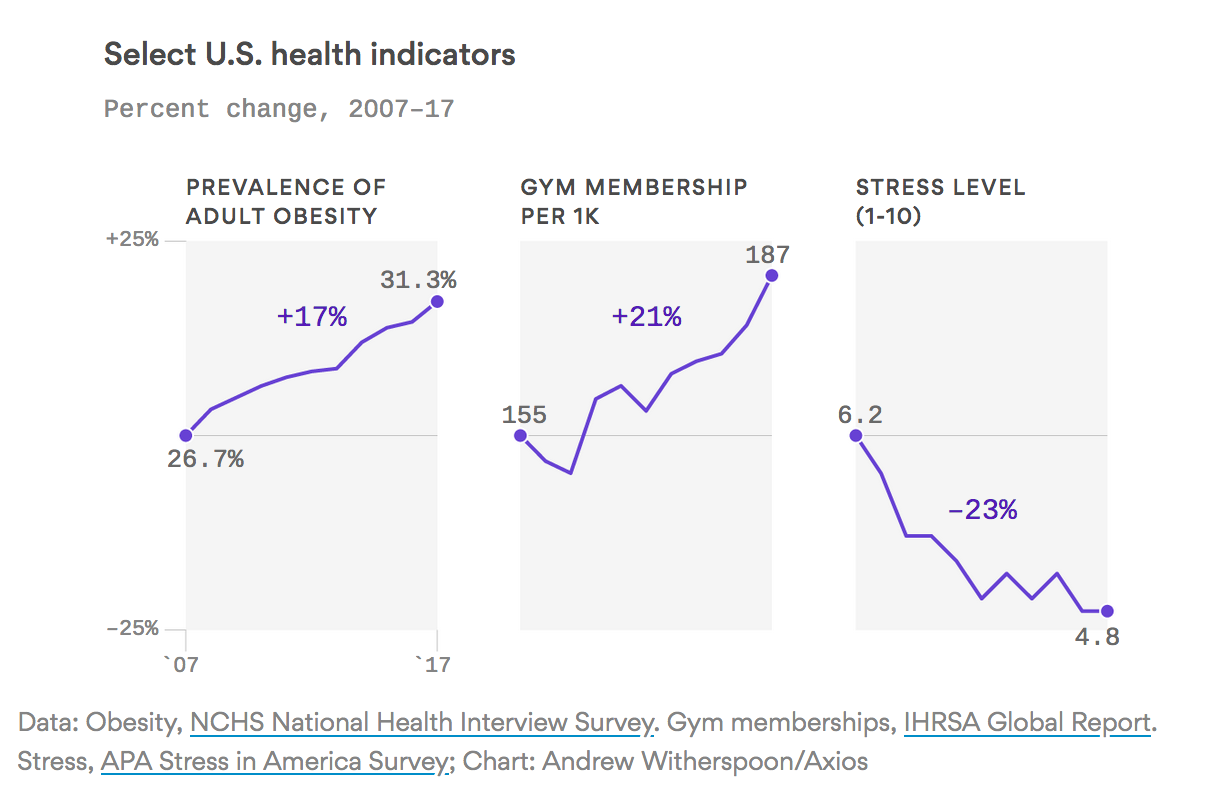

Axios has an informative article about obesity, and the various remedies such as exercising, diets, and so on. Their headline is: "Health and wellness are booming, but we're fatter than ever." They have compiled some data, shown in a triplet of graphs:

The problem of obesity is complex, and fascinating from a data perspective. I devoted an entire chapter of Numbersense (link) to issues around measuring obesity.

There is much more underneath the surface than what is presented here. Let me unpack the layers of complexity.

Correlation is not Causation

The simplest issue to explain - just because statisticians have been screaming about it forever. If you look at the obesity chart and the gym chart, it is entirely accurate to say that gym membership has been rising in lock step with obesity rate during this decade. Both metrics rose by roughly 20%; and so it is very tempting to argue that going to gyms makes you fatter.

Of course, if you draw that conclusion, you've just been disinvited from the party of statisticians.

Ecological Fallacy

Here's the disturbing bit: the charts are also compatible with the opposite conclusion - that gym membership reduces obesity. This is an example of why it's so hard to interpret observational data.

Note that the data analyst collapsed a 2x2 matrix into two aggregate rates. Imagine four types of people: those with or without gym membership, crossed with those who are obese or not obese. When you're aware of the four types, you should realize that the rate of obesity, aggregated across gym membership, is not a great metric. It's pretty obvious that the obesity rate of those who are gym members is lower than that of those who do not have membership. The average rate paints them with the same brush.

In the same way, gym membership, aggregated across obese and not obese people, is not a great metric.

You can reasonably assume that obesity rate for the gym members should be lower than the average obesity rate, for example, if the average is 25%, then perhaps the obesity rate for non-gym members is 15%.

It's possible that the 15% rate has not changed over time but if the obesity rate of the non-gym-members increases, the overall obesity rate will increase (note that there are five times as many non-gym-members as there are gym members). The 15% rate for gym members could even have improved, and the overall obesity rate could still decline to 30% - it just requires the non-gym-members to get even more obese.

When aggregating the rates, some information is lost, and that weakens our ability to draw conclusions about individuals.

Indirect Metrics

Gym membership is not the same as gym usage. The gym's ability to influence obesity would require usage, not just membership.

CDC Diet Recommendation

The bit about the CDC complaining that people don't consume the recommended levels of fruits and vegetables makes me wonder if their problem formulation is overly simplistic. The dietary guidelines appear to be an optimization of nutritional benefits. But the real problem is to maximize nutritional benefits under a budget constraint. Each item in the basket of recommended foods delivers an amount of benefits at a level of cost. The total cost can't exceed the household budget.

For anyone taking a traditional class on optimization, "the diet problem" is often the first problem discussed. Here is one exposition of the diet problem.