Grouponomics, and the power of counterfactual thinking

Felix Salmon wrote thousands of words to convince himself that Groupon has a viable business model. I have a lot of respect for Felix and love his blog, but he missed a key issue here. Maybe he drank the Koolaid, or perhaps I am an even bigger skeptic than Felix is. I don't have a rebuttal as much as an alternative narrative.

***

Let's start with his neighborhood restaurant example:

At Giorgio's, for instance, diners paid $15 for their Groupon -- which gave them $30 of food. But dinner for two at Giorgio's, with some kind of alcohol, can easily run to $100 or more. So even after knocking $22.50 off the bill (remember that Giorgio's kept $7.50 of the proceeds of Groupon), the restaurant would often still make money.

This is a bit complicated. We can trace how the cash flows. For Groupon, diners pay them $15, and they keep half of that, $7.50. For the diners, they paid Groupon $15 (now worth $30 spending), and so they pay Giorgio's $70; in other words, they paid $85 out of pocket for a meal worth $100 without Groupon. Giorgio's take in $70 from the diners plus $7.50 coming from Groupon for a meal worth $100.

Where I think Felix missed the mark is when he reasoned:

If you're already a regular somewhere, of course, then buying its Groupon is a no-brainer. And the restaurateur won't begrudge you the savings, either: all restaurant owners want to treat their regulars as well as they can.

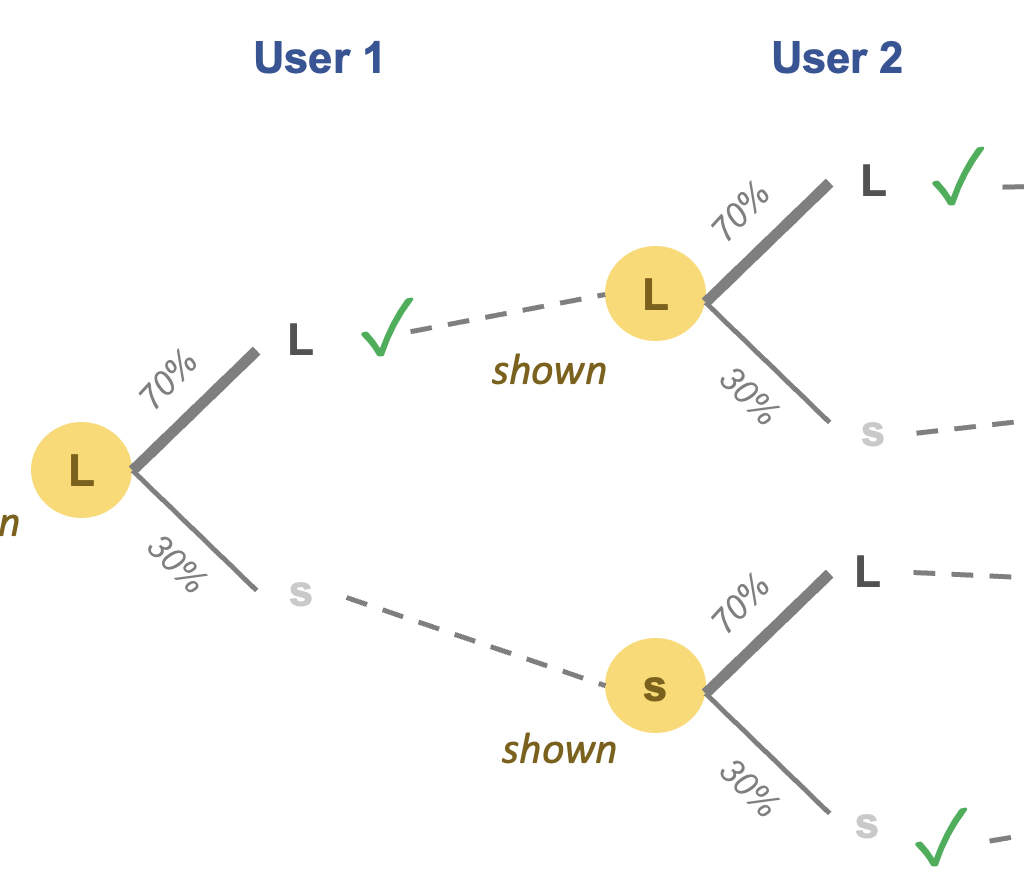

I violently agree with the first sentence -- that Groupon-type deals are a gold mine for regular customers. The second sentence, however, doesn't make sense. Go back to the example. For a new customer, Giorgio's makes $77.50 that it would otherwise not make without Groupon. For a regular customer, Giorgio gives up $22.50 that it would otherwise have taken in without Groupon. So, for every 3.4 regulars who use the coupon, Groupon has to generate at least 1 new customer for Giorgio's to break even.

If Giorgio's does not achieve that ratio of new to regular Groupon-wielding customers, then Giorgio's could end up earning less total revenues despite having served more diners/meals.

So, I don't think the Groupon model is the kind of slam dunk Felix seems to think it is. Only if certain conditions are met will the merchants gain anything from Groupon:

- the value of the coupon has to be a fraction of the total spending at the merchant; in this example, the diners spent more than 3 times the face value of the coupon. What if the diners spend exactly $30? Then Giorgio’s loses $22.50 on each regular customer and earns $7.50 on each new customer, meaning that every 3 new customers pay for each regular’s discount. Not very attractive numbers at all.

- the lifetime value of the new customer must be high. Felix also mentions this. The business case is better if the new customers keep coming back, and pay undiscounted rates.

- the coupons are available in limited quantities and at limited times. The more times regulars use these coupons, the bigger the revenue hole the merchant finds itself facing.

- the merchant has no other means of attracting new customers. Our computation assumed that the new customer would never contribute any revenues unless Groupon is in the picture.

This analysis deals with the business model of a merchant using Groupon; even when the merchant loses, Groupon will still make money.

***

How is this related to statistical thinking, you might ask? Why am I wasting ink talking about this?

What is missing in the typical narrative about Groupon – the one promoted by the company – is the “counterfactual”. The counterfactual is a powerful concept embedded in statistical theory. In order to evaluate the data in front of us, we must imagine an alternative world (the counterfactual) in which we allow the data to present themselves differently. To understand how medicine X might affect you, you can't just measure what happened after you took medicine X; you must also consider what might have happened if you took medicine Y and/or nothing at all.

So, instead of just thinking about the new customers brought in by Groupon, we must also consider the world without Groupon. In the world without Groupon, the regulars pay $100 for their meals, and the new customers pay $0 or some other amount (if Giorgio’s has other ways to attract them). This allows us to realize that the insertion of Groupon into that world would lower the intake from regulars while simultaneously raising the intake from new customers. For the merchant, whether Groupon is a net benefit depends on the balance between those two numbers.

This is related to the concept of opportunity cost in economics. When evaluating the value of an investment, we can’t just tally up the returns of said investment; we have to compare those returns to the returns of doing something else such as keeping the money in the bank.