Never a failed test fails the statistical test

Lance Armstrong is being accused of doping by former teammates, many of whom directly helped him to win 7 Tour de France championships. According to this Yahoo! report, Armstrong's response, via Twitter, was:

20+ year career. 500 drug controls worldwide, in and out of competition. Never a failed test. I rest my case.

***

I don't know if Armstrong doped or not. Given that his racing days are years in the rear-view mirror, there is little chance we will ever have direct evidence either way.

However, as I pointed out in Chapter 4 in Numbers Rule Your World, "never a failed test" is not a great basis on which to rest one's case!

We have quite a few examples of athletes who never failed any drug test during their competitive careers but later confessed to doping. Marion Jones and Bjarne Riis are two examples I used in the book. Why is this the case?

The sad truth of steroid testing is that most dopers do not test positive. A recent example (discussed here) illustrates that about 50% of dopers would pass the test -- and that was measured in a controlled laboratory experiment. The reason for such high false negative rates is that the anti-doping labs want to minimize the chance of a false positive error. The underlying statistics dictate a trade-off between false positives and false negatives; the harder one tries to eliminate false positives, the more false negative results will be produced!

I call for more false positives in drug testing in this post.

***

The media has gotten the statistics totally backwards.

On the one hand, they faithfully report the colorful stories of athletes who fail drug tests pleading their innocence. (I have written about the Spanish cyclist Alberto Contador here.) On the other hand, they unquestioningly report athletes who claim "hundreds of negative tests" prove their honesty. Putting these two together implies that the media believes that negative test results are highly reliable while positive test results are unreliable.

The reality is just the opposite. When an athlete tests positive, it's almost sure that he/she has doped. Sure, most of the clean athletes will test negative but what is often missed is that the majority of dopers will also test negative.

We don't need to do any computation to see that this is true. In most major sports competitions, the proportion of tests declared positive is typically below 1%. If you believe that the proportion of dopers is higher than 1%, then it is 100% certain that some dopers got away. If you believe 10% are dopers, then at least 9 out of 10 dopers will test negative!

***

While researching the book, I learned that trying to catch dopers is extraordinarily hard. Here are some reasons why a doping athlete could get a negative test result:

- he's using a drug that is also produced naturally by the body, which means that the test needs to detect "unnatural" levels of the chemical, rather than the presence of a foreign substance

- he's using a new drug that has no test yet

- he's using "masking agents" that hide the performance enhancing drugs

- he's used steroids during training but not during competition (many sports don't conduct out-of-season testing, and even if they do, you can't possibly test all athletes all the time)

- he's received a "therapeutic use exemption" (I'm not sure why the sports bodies have never disclosed which athletes have been allowed to use which drugs based on TUE)

- he's following a drug schedule that attempts to evade testing

Those are not the only reasons. Notice that all of these tactics are not replicable in a lab so the accuracy rates reported by labs are almost for sure overly optimistic.

***

Armstrong's latest accuser is Tyler Hamilton, who features in my book. When I first started writing, he had failed one test, got banned, came back, and failed another test. Even after the second failed test, he had maintained his innocence. By the time I finished writing, he had come back yet again and failed a third test, upon which he retired.

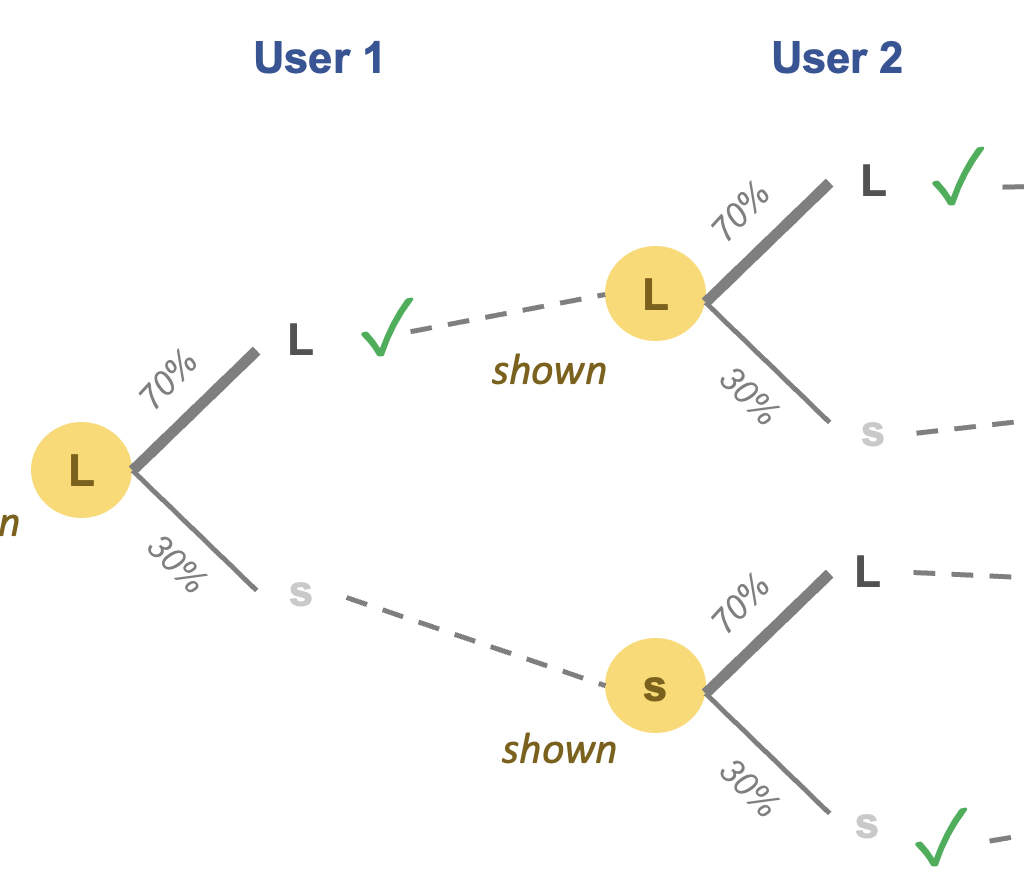

One other statistical point of note: test results for a given individual are not necessarily "independent"! It's not too surprising that people like Hamilton kept failing tests while other dopers like Marion Jones kept passing tests. A failed test indicates that the doping program of that athlete isn't foolproof, and we should expect that athlete to have a higher chance of failing again in the future. A negative test, by contrast, may indicate that the doping program is robust against the testing regime. (In Jones's case, she was using a new designer steroid that took years for the test labs to notice.)