Reality check on the long tail

Another over-sold story?

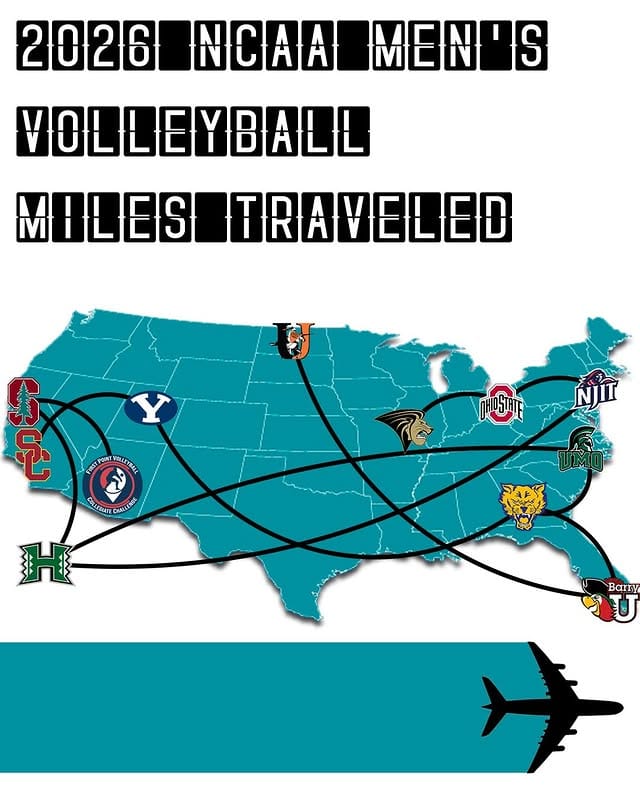

Some time ago, there was a lot of hype about how new tech will demolish the superstar effect in entertainment sales because all the little titles in the long tail will be exposed to consumers. I recall Amazon being labeled the shiny example of a company that made profits off the long tail (as opposed to the boring top of the distribution). I still remember this graphic from Wired (link):

A reader Patrick S. pointed me to a study of music services that pronounces "the death of the long tail" (Warning: they want your email address in order to read the full report. The gist of the report was written up in this other blog.). Reading these pieces, one wonders whether this long-tail miracle even existed in the first place. The main thrust of the argument is that the new digital subscription/music services have not changed the allocation of spoils amongst artists. The little guys out in the long tail are still earning much less of a (shrinking) pie.

The long tail is an example of those intuitive, elegant scientific concepts that are much less impactful in the real world than claimed. Here is what I think caught some smart people on the wrong foot:

- The distribution of profits has always been much more extreme than the kind of ballpark graphics (like the Wired chart above) shows. The new study for example suggests that the top 1 percent earned 77 percent of all the money. This is much more extreme than the 80/20 rule. From the graphical perpective, you can think of the distribution as one very tall spike and a very flat, very long tail.

- The cumulative weight of the very flat, very long tail is still not that heavy compared to the one spike. Even if you manage to increase the size of the tail by 10 percent, it still amounts to a small number.

- The above assumes you can increase the size of the tail. But it is quite hard to do. One reason is that the tail consists of millions of little pieces, which don't necessarily move in sync.

- The second, and more important reason, is that titles or artists don't randomly end up in the tail. If a title is in the tail, it's an indicator that the artist or title is not appealing to the mass audience.

- We fell prey to the romantic notion that there are some unjustly neglected artists, and rejoice in the idea that the long-tail effect may allow a few of these to reverse their fortunes. But a few outliers do not change the overall distribution.

***

The report's authors also make this observation:

Ultimately it is the relatively niche group of engaged music aficionados that have most interest in discovering as diverse a range of music as possible. Most mainstream consumers want leading by the hand to the very top slither of music catalogue. This is why radio has held its own for so long and why curated and programmed music services are so important for engaging the masses with digital.

While I believe this story, I should note that there is no quantitative evidence provided (at least not in the summary). If this is true, it has important implications for anyone in the business of "personalizing" marketing to consumers.