The case for more false positives in anti-doping testing

Here comes the promised second installment to my recent post on anti-doping in which I argue that we should pay a lot more attention to false negatives. Here's the last paragraph:

For me, the difficult question in the statistics of anti-doping is whether the current system is too lenient to dopers. If the risk of getting caught is low, the deterrence value of drug testing is weak. In order to catch more dopers, we have to accept a higher chance (than 0.1%) of accusing the wrong athletes. That is the price to be paid.

Note that this post has been contributed to the Statistics Forum (link), which is a new blog sponsored by the American Statistical Association and edited by Andrew Gelman, and is reprinted here. You can click on the link above or scroll below to read the full post.

***

In a prior post on my book blog, I suggested that anti-doping authorities are currently paying too much attention to the false positive problem, and they ought to face up to the false negative problem.

This thought was triggered by the following sentence in Ross Tucker's informative article (on the Science of Sport blog) about the biological passport, a new weapon in the fight against doping in sports (my italics):

the downside, of course, is that cyclists who are doping can still go undetected, but there is this compromise between "cavalier" testing with high risk of false positives and the desire to catch every doper.

Kudos to Tucker for even mentioning the possibility of false negatives, that is, doping athletes who escape detection in spite of extensive testing. Most media reports on doping do not even acknowledge this issue: reporters often repeat claims by accused dopers that "they had tested negative 100 times before" but a negative test has little value because of the high incidence of false negative errors.

Unfortunately, having surfaced the problem, Tucker failed to ask difficult questions, opting to take the common stance that the overriding concern is minimizing false positive errors. This attitude is evident in the description of the false negative issue as "the desire to catch every doper", or put differently, the desire to achieve zero false negative error.

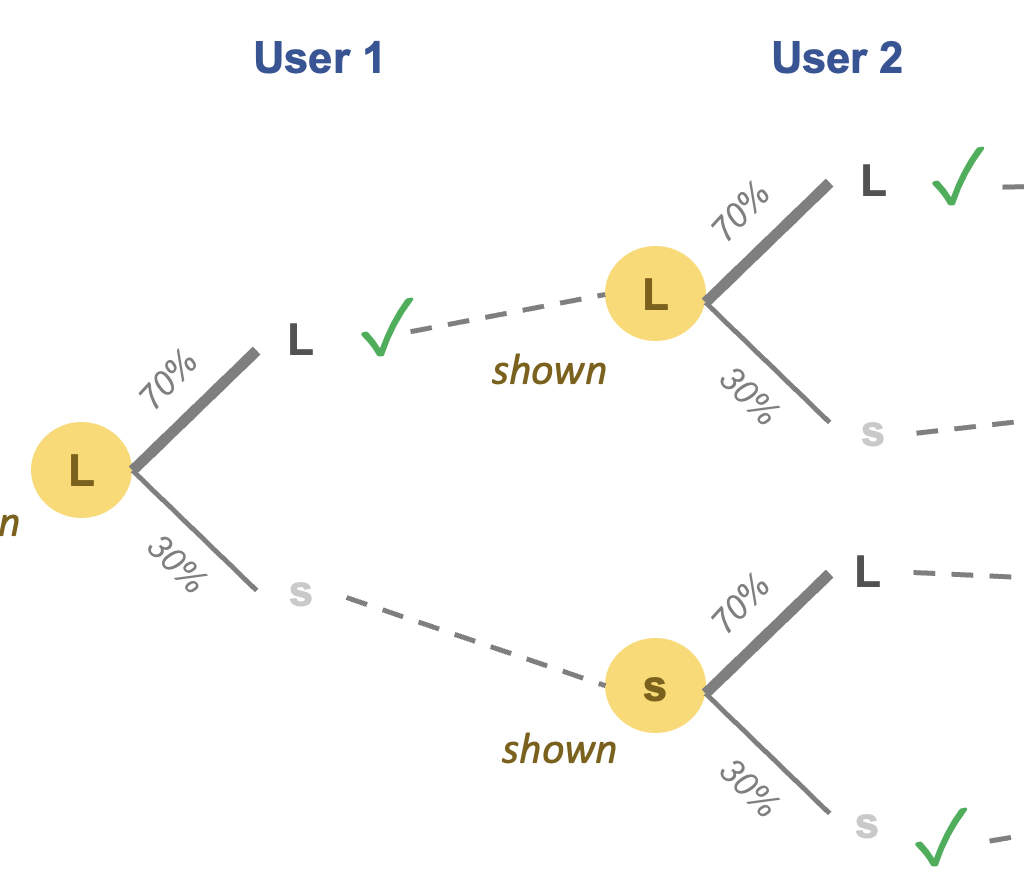

In fact, the opposite is true of today's drug testing regime. There is a desire to achieve near-zero false positive errors. The inevitable statistical result of that objective is to admit large quantities of false negative errors. Elsewhere in Tucker's article, he cited a study in which the researchers desired a false positive rate of only 0.1% (arguing that 1% would be too high for comfort). The flip side, which Tucker also reported (without comment), is that the same test picked up only "5 out of 11 doping athletes", which means the false negative rate was over 50%!

Thus, it is unfair to brand the people complaining about false negatives as hoping to "catch every doper"!

***

The implication of high false-negative errors is twofold: (1) the majority of dopers would escape undetected and unpunished so that those testing positive can consider themselves rather "unlucky"; and (2) the negative predictive value of anti-doping tests is low, making a mockery of accused dopers who point to large numbers of prior negative results.

The anti-doping authorities today concern themselves with minimizing false positives, and turn their heads away from the false negative issue. As I explain in Chapter 4 of Numbers Rule Your World (link), there is little hope of reform from within: outside lab experiments, false negative errors are invisible because few athletes would voluntarily disgrace themselves after passing drug tests! (The few cases of admission occurred long after the athletes retired.)

***

What we just discussed are results from lab experiments; what is happening in the real world is likely to be even worse. Any error estimate should be treated skeptically as the best-case scenario.

A useful analogy is the testing of the ballistic missile defense system. At the early state of development, the interceptors are asked to destroy known targets, objects of known number, shape and trajectory launched from known locations at known times.

Similarly, the error rates of anti-doping tests are established by testing athletes in a lab setting, known to be doping, with a known doping schedule, using known compounds at known dosage and known timing. The real-life problem of catching dopers is significantly tougher.

***

For me, the difficult question in the statistics of anti-doping is whether the current system is too lenient to dopers. If the risk of getting caught is low, the deterrence value of drug testing is weak. In order to catch more dopers, we have to accept a higher chance (than 0.1%) of accusing the wrong athletes. That is the price to be paid.

Where do you stand on this?