Why should we care about these studies?

Reader Joe M. points us to this article from Slate (via Kottke).

Supposedly we are to believe that our success/happiness/fate/etc. is predetermined by the alphabetical rank of our name. This was something that the Freakonomics team has already pitched to us years ago, when they recited the claim that you have a "higher chance" of winning the Nobel Prize if your surname begins with an "A" than a "Z".

I really don't care enough about these studies to give them a serious look. Just on the surface, I have many doubts about this line of research:

- In places such as China, names are not made up of alphabets. What is the relevant hypothesis for these countries? If you can specify the hypothesis without first looking at the data, and your hypothesis proves correct, then maybe I'll pay some attention.

- Lots of things make people happy or successful. The magnitude of the effect matters. It is very likely that if it exists, this "name effect" is extremely small - you'd only be able to see it if you control for every other factor. It is very likely that many other factors have a larger impact on your happiness and success than this "name effect". So, if you want happiness or success, you should spend your time and energy on those other things, rather than on naming babies. This is the classic fallacy in statistics of confusing "statistical significance" with "practical significance".

- I haven't seen the following type of test of intervention: have randomly selected "Z" named kids change their names to "A" names, and track to see if they end up being more successful than those who did not change their names.

- The above test is unlikely to yield the result we want. If the "name effect" is strong, it should be noticeable and if noticed, it should lead to a large shift in naming conventions; we should see parents preferring "A", "B", "C" names. We don't see this. Why?

***

For those who want to dig deeper, the following excerpt on how the researchers analyzed various studies makes for fascinating reading: (italics are theirs, bolding by me)

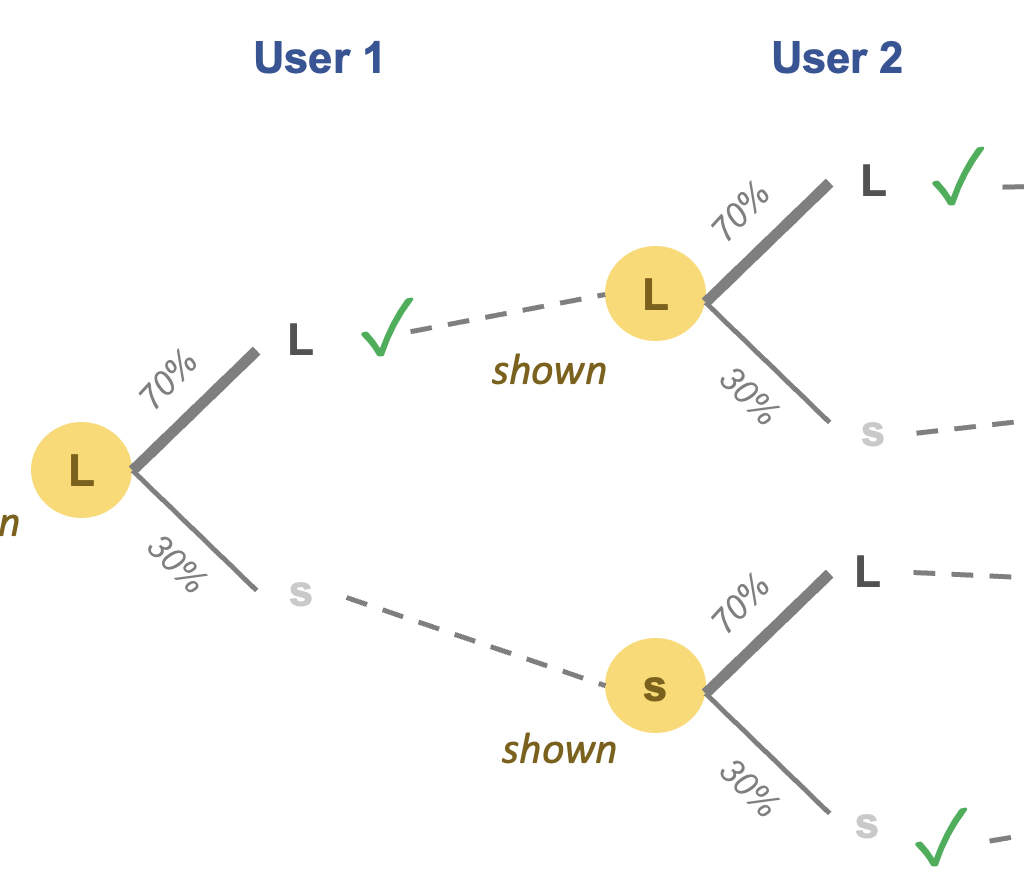

1.) Business school students were invited by e-mail to receive up to four free tickets to attend a basketball game. The students were told there was a limited supply and that tickets would be given away on a first-come, first-serve basis. Seventy-six students put in requests before all the tickets were spoken for. Average response time was 23 minutes (students love getting free stuff!). Response time correlated negatively with alphabetic rank. In other words, students at the end of the alphabet put their bids in, on average, earliest.

2.) E-mails were sent out to adults offering them $500 to participate in a survey. Average response time was between six and seven hours. The same negative correlation between response time and alphabetic rank was observed, but only when the researchers looked at the names the respondents were born with. When Carlson and Conard looked at married names or names changed for some other reason, the correlation dwindled to insignificance. This, they conclude, demonstrates that the "last name effect" derives from "a childhood response tendency." Only people who grew up with a name at the back of the alphabet demonstrated truly Pavlovian responses to the $500 offer.

3.) Students of drinking age in a wine-appreciation class were told, verbally, that they could receive $5 and a free bottle of wine if they participated in a wine survey. Average response time was about six hours. Again, a negative correlation was found between response time and alphabetic rank. The R-Zs responded, on average, about an hour faster than the A-Is. Carlson and Conard also compared the responders as a whole with the students who didn't respond. The R-Zs were more likely to be responders.

4.) Undergraduate students who were paid to participate in this and other studies were asked to imagine the following situation: You need a new backpack and as you pass a bookstore you see that it's selling brand-name backpacks for 20 percent off "while supplies last." But you don't have your wallet with you! It would take you 15 minutes to go home, get your wallet, and come back to the store. Do you do that right away? Yet again there was a negative correlation between (hypothetical) response time and alphabetic rank. The R-Zs were more likely to say they would trudge home and back to take advantage of the sale.

Notice that in each case, the researchers went into the study with one hypothesis and came out with a modified conclusion *after* looking at the data. It is almost surely the case that the hypothesis was either left vague ("there is negative correlation") or was abandoned in the face of contradicting data ("A-K names are different from L-Z names"). The result would be more credible if the researchers had proposed that A-P names would be different from R-Z names *without* looking at the data first. Same thing with the birth name versus married name.

By forming and also verifying hypotheses on the same data, these researchers are running a very high risk of false positive findings. In the A-R finding, for example, they have in effect simultaneously checked at least 25 hypotheses (bisecting the group at A, at B, ..., at Y) and possibly more (since they may not have limited themselves to binary partitions). In typical statistical practice, we would need to use a p-value much higher than the conventional 5% to "accept" such findings. Put differently, if the conventional 5% were to be used, the chance of a false positive is not 5% as advertised but some shockingly large number that you'd be ashamed to report. (For those curious, look up the problem of multiple comparisons.)

Also, I worry about publication bias. We have here four examples of this purported effect. What if researchers have looked at a hundred other examples, and those didn't show this effect, and were shoved away?

Contrary to Freakonomics, I do not recommend changing your name to Aaron or Audrey any time soon.