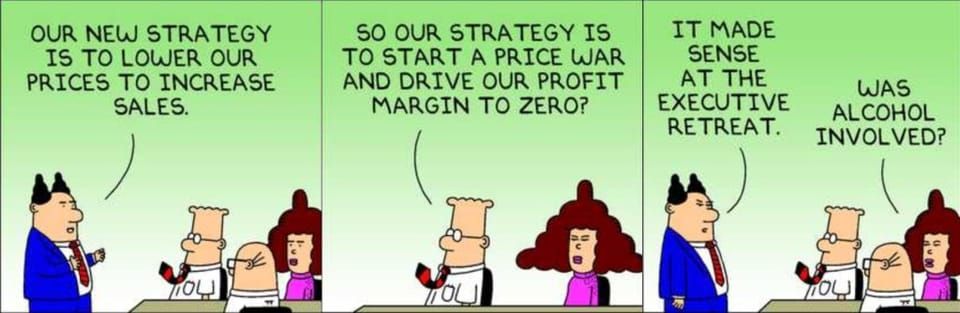

Wishful thinking using statistics

Do observational data really support the theory that weight-loss drugs have caused the average Norwegian to be less obese?

In this piece (link), John Burn-Murdoch at the Financial Times (he's the guy who made some nice Covid-19 graphs) advances a theory of "peak obesity" saying that the new weight-loss drugs will reverse the trend of increasing obesity around the world, pointing to the recent CDC release showing a slight dip in U.S. obesity rate as evidence.

Here is a funny quote from his article:

More likely than not, this will prove another case of “where the US leads, others will follow”. In Denmark, home of Ozempic and Wegovy creator Novo Nordisk, 3 per cent of adults were using the new drugs by the end of 2023. The decades-long climb in the obesity rate slowed to a crawl that same year, and declined among several age groups.

When only 3 percent of Norwegians are using these drugs, the impact on the population-wide number is highly limited. I don't find this argument convincing.

Imagine one of these patients whose use of these drugs has directly lowered the obesity rate in Norway. The person has to be obese, and is taking the drug to treat obesity (rather than treating diabetes, its original use). The person has been taking the drug for long enough time for the effect to become detectable, probably a year, depending on how the original studies measured impact. Because the flattening of the obesity rate line happened during 2023, this person must have started the treatment before 2023, or in the early part of 2023.

The person must not have stopped taking the drug. The person must have lost enough weight so as to cross the boundary from obese to not obese (BMI = 30). In other words, the more obese the person is, the more unlikely this person's improvement can move the average obesity rate down because as far as I know, Novo Nordisk is claiming around 15% weight loss, and not claiming that an extremely obese person could become non-obese after a year of Ozempic or Wegovy. A severely obese person is defined as having BMI over 40. A weight drop of 15% reduces BMI of 40 to 34, which is still above the obesity threshold of 30. For simplicity, we can think of someone with BMI 30-35 as most likely to help lower the obesity rate if their BMI drops below 30 as a result of taking the drugs.

Further, as with all drugs, only a portion of those who take them would realize benefits because no drug is 100% effective.

What we know is 3 percent of all adults were taking the drugs at year end 2023. Is that a large enough slice of the population to affect the obesity rate? I doubt it.

***

Last but not least, there is a hidden model behind the FT claim - which explains the change in obesity rate using a single factor of weight-loss drugs. This model assumes that the people who successfully lost weight after taking these drugs did not undertake other activities (such as exercise or dieting) which also may lead to weight loss. Since this is data analysis, not a designed study, I don't think we know what other measures people have taken.