Another type of algo pricing

How does dynamic pricing work?

In my previous take on "algorithmic pricing," I deliberately glossed over one nuance.

Typically, the inputs to a pricing algorithm are demographics, behavioral data (e.g. how many times the user has revisited the product page), estimated price sensitivity, and so on. Most of these are data about the individual customer. Thus, it has been shaded as "surveillance pricing."

It is also possible to build a pricing model using purely supply and demand data that do not identify individuals. How much inventory does the retailer have? What's the projected demand? How do price changes affect the demand? At what price does the retailer generate maximum profits?

Demand forecasting is likely to benefit from "surveillance" data such as the frequency of users browsing the item's page, or placing it in the shopping cart. In this setting, however, the data will be aggregated. That's because this design allows the price of an item to change over time but not to vary across individuals at a given moment.

The observations of Consumer Reports do not suggest this type of pricing algorithm; thus, I didn't mention it in the other post.

Dynamic pricing is normal in various industries. Airlines, hotels and the hospitality industry have long priced their products based on supply and demand data. That's why plane tickets and rooms get more expensive, the closer it is to the use date. (But excess inventory might go on fire sale for last-minute bookings.)

Customers end up paying different prices for similar products (note: never the same room or seat at the same time) but it doesn't feel unfair. That's because a room on Christmas Eve is clearly more valuable than the same room the week before. Besides, everyone who's willing to lock down the reservation months in advance get a discount. This dynamic pricing isn't offensive.

Differential grocery prices don't give the same vibes. The same can of tomatoes isn't worth more from one week to another, and sellers can order more inventory instead of hiking prices if demand exceeds expectation.

Turkey during Thanksgiving week doesn't have to be more expensive; the markets can stock up. Consider the alternative of dynamically adjusting prices. Imagine there are 10 turkeys on the shelf, and 50 shoppers will be looking to buy a turkey. If the current price is affordable to everyone, then the sales become effectively first-come, first-served. This feels fair because if you want a turkey, you hussle there before the others. If the vendor raises the price to price out 40 of the 50 shoppers, then the turkeys end up with the highest bidders. In reality, the algorithm isn't so precise but the overall effect is to sell the birds to those willing and able to pay more.

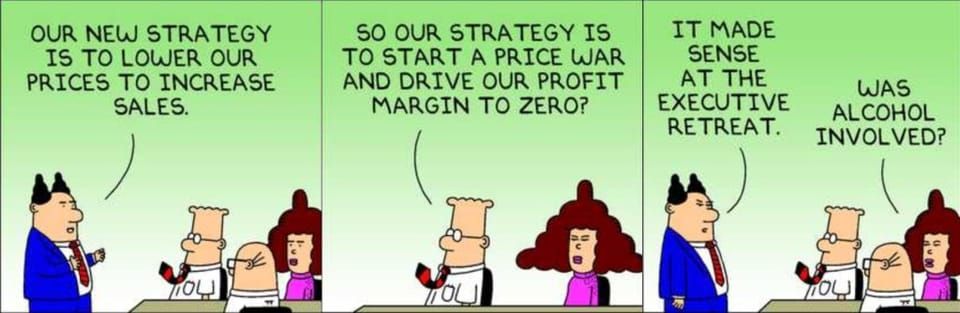

Economists may praise the dynamic pricing setting as more "optimal." It certainly maximizes the total revenues received by the sellers. The average customer of everyday items finds it unfair. Perhaps part of the opposition is against asymmetric application. I find it hard to believe that the same dynamic pricing algorithm would be allowed to lower prices in response to poor demand. Each such price adjustment is a bet by the seller that the price drop would generate sufficient additional purchases to pay for itself. It represents trading a sure thing for an uncertainty.

Interestingly, supermarkets don't tend to play with lead times, unlike airlines or hotels. Almost all grocery items have best-before dates but only a few stores I know put discounts on items that are about to expire. Why? I'm not sure. Too much administrative hassle? Too many customers shifting from paying list prices? Do you have a guess?