Blood clots: is there a there

Kaiser looks at the controversy over blood clots and the Astrazeneca vaccine.

A number of mostly European countries have suspended administering the Astrazeneca-Oxford vaccine in order to investigate whether it has led to blood clots. These decisions have aroused angry reactions from the media. Here's an opinion column by Prof. Spiegelhalter that captures the mainstream view.

Many reporters have mis-spoken when they say the countries have banned the vaccine. They are pausing new inoculations so that the health authorities can assess the situation.

Spiegelhalter's argument - which was also that of Astrazeneca - relies on comparing the incidence rate of blood clots among those who have been vaccinated (millions) and the incidence rate of blood clots in the general worldwide population. He estimates that about 100 people in any given week experience blood clots, while so far only 30 cases have been reported post-vaccination (across many weeks).

As with any statistical argument, we should outline the unspoken assumptions under which this argument will prevail.

First, we must assume that the system used to collect information about blood clots is reliable and mostly complete. Spiegelhalter says the "yellow card" system used in the U.K. for reporting side effects has produced far fewer side effects than during the clinical trials. He interprets this as evidence that the vaccine is even safer than advertised. Another possibility is that the side effects are being under-counted. The hard part is to figure out by how much.

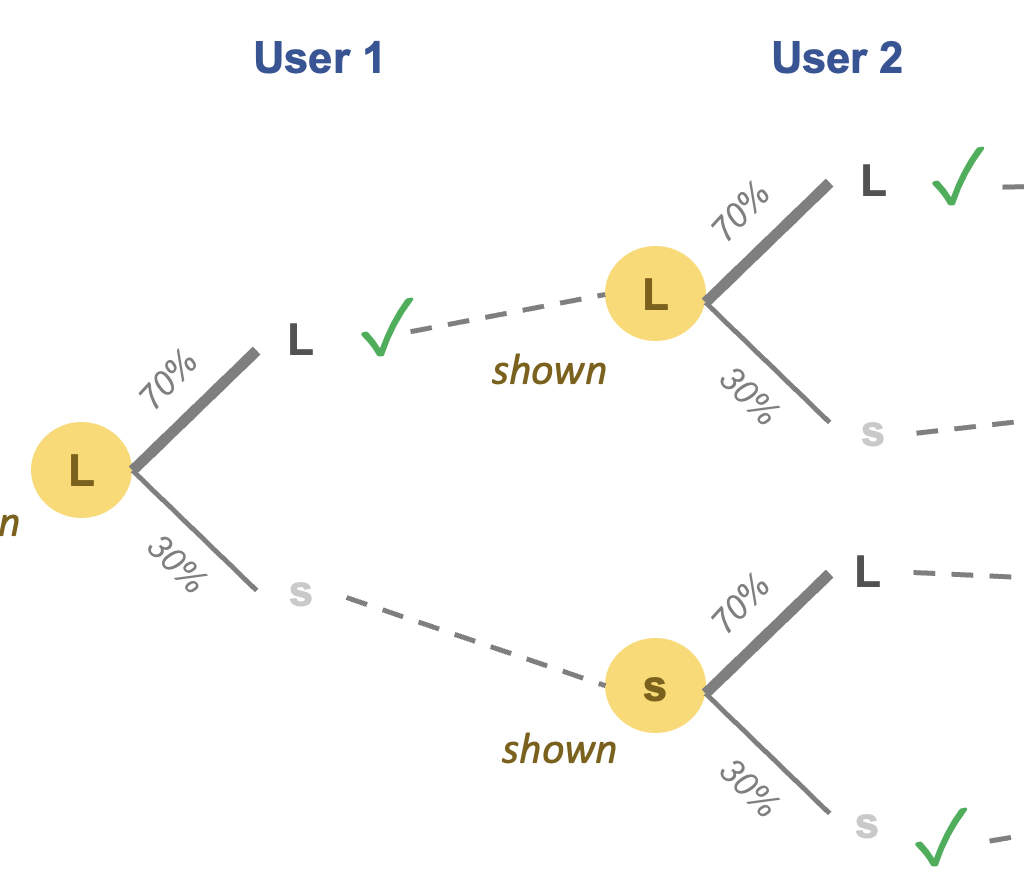

Second, we must assume that the people who have been vaccinated so far is a random sample of the entire worldwide population. On second thought, it's not obvious that the rate of blood clots should be the same in every country, or every age group. There may also be seasonality in the condition - the data on the vaccine has come only from the spring season while the general data are averaged over the year.

Third, we must assume that the characteristics of the people who have reported blood clots are similar to the average person who gets blood clots in an average year. It's worth noting there are reports of unusual blood clots in young vaccinated people. The problem may be blood clots in young people, not all people.

Fourth, we must assume that all blood clots are alike. Are there different types of blood clots? Are the reported blood clots similar to the average blood clot? Depending on the answer, we may need an incidence rate for specific types of blood clots (and also for specific age groups).

Fifth, we must assume the outcomes of those who reported blood clots post vaccination are similar to those in any given year. In particular, several deaths have been reported. Is the rate of death among those who experienced blood clots abnormal?

Sixth, I'd like to tally the incidence of blood clots in the unvaccinated populations as well. According to Spiegelhalter's back-of-the-envelope calculation, the incidence of blood clots is actually far fewer than expected (only 30 cases in several weeks vs 100 weekly), and so we should expect the data to reveal that the chance of experiencing blood clots in the last few weeks was much higher among the unvaccinated than among the vaccinated - assuming those weeks were normal weeks. (If this proves true, it raises the prospect that vaccination is protective against blood clots!)

Seventh, we must also assume that there is no one-time anomalous event that is causing a spike in blood clots. Some reports claim that there might be a bad batch of vaccine. It is possible for both of the following to be true: that the Astrazeneca-Oxford vaccine does not cause excessive blood clots, and that a particular batch of the vaccine caused an excess of blood clots among those received those doses.

Eighth, we must assume that the several weeks of data collected about the vaccine are fully representative of ongoing data. There is a precautionary tale here. At any moment in this pandemic so far, if we took the cumulative data and annualized them, we would have produced horrible forecasts of the future.

***

That's a lot of assumptions and the list is not necessarily complete. What we are dealing with is another observational (i.e. real world) study. Without the randomization of randomized clinical trials, it's just really hard to connect an effect to a cause.

Making assumptions is not fatal in statistical analyses - on the contrary, every statistical argument contains some set of assumptions. If I were conducting this investigation, I'd focus on collecting data to check the above assumptions. I believe the mainstream view may prove correct; this would imply most of the above assumptions hold.

It is also true that the current known incidence rate is small, benefits outweigh the side effects, etc. Notice that this is a different line of argument. The statistical argument claims the blood clots are normal and thus there is no problem at all. This second argument accepts the blood clots as abnormal but an acceptable price to pay; it is unnecessary if one agrees with the statistical argument.

***

I don't think it's wrong for European politicians to take a cautious approach. I wish the experts were not all over the media slamming the politicians and citizens about their alleged failure to understand science - because such ferocious rhetoric is drawing unnecessary attention to what should be a routine process. Just say you support a quick investigation, Astrazeneca should cooperate and provide any necessary data, and you expect the vaccinations will resume in short order because this is likely a false alarm.

P.S. [3/17/2021] Just listened to the hour-long press conference by the European Medicines Agency outlining the process of the investigation. They clearly state that they don't believe the extent of the problem would ever outweigh the benefits of the vaccine, but they also say the specific circumstances of those cases require examination. They expect to come to a quick conclusion, by Thursday afternoon.

Many of the issues mentioned in this post were brought up, such as specific types of blood clots, batches of vaccines (or manufacturers), and establishing base rates for specific time frames. The committee of experts will be looking into those and other factors. One reporter asked an important question - whether there will be a biological investigation to go along with the statistical analysis.

The scientist representing EMA mentioned the back-of-the-envelope calculation that would indicate that people who were vaccinated were far less likely than normal to have blood clots. I don't think this is their strongest argument; unless the vaccine somehow prevents blood clots, you'd have expected the frequency to be roughly normal - and if it's not, you now have to go down the rabbit hole of explaining the biases in the vaccinated population, which I can assure you opens up a can of worms.

Also worth noting (which I did in a comment below) is that both sides could be right. It may be that the vaccine causes excessive, potentially fatal blood clots of a specific type in a specific subpopulation. That means the vaccine is still safe for almost everyone. This bolsters the cost-benefit argument. The end result may be just a warning about a rare side effect for people with specific conditions.