Know your data 47: bait and switch prices

Can we measure inflation using in-store prices?

Long-time reader Mark P. sent me to this Guardian investigation of pricing discrepancies in "dollar stores" in the U.S. (link)

The dollar store is really the five-dollar store these days. I don't think one can find anything in a dollar store that costs a dollar!

The reporter did a great job finding customers and former employees of these stores to tell their stories. Many of the customers live in isolated areas, and on tight budgets. A dollar store is often the only retailer within walking distance to where they live, and so in a sense, they represent a captive audience.

The headline is bait-and-switch pricing. It turns out that these dollar stores (the article names two chains: Dollar General, and Family Dollar) frequently charges customers higher prices than the advertised shelf prices.

It's not a one-time anomaly. In some stores, as much as 80% of the register prices have been found to be higher than the respective shelf prices! The differences aren't mere rounding up. Examples given in the article include $5 frozen pizzas charged $7.65, and $11 npaper towels charged $15.50. Even after authorities have complained about this practice, and even assessed penalties, many such stores continue to bait and switch.

The situation is really shameful:

Dollar General stores have failed more than 4,300 government price-accuracy inspections in 23 states since January 2022, a Guardian review found. Family Dollar stores have failed more than 2,100 price inspections in 20 states over the same time span, the review found.

"Industry watchers" want our pity. They claim that stores do not have sufficient staff to update shelf prices, leading to pricing discrepancies. In other words, they're saying that the register prices are correct, and the shelf prices are incorrect.

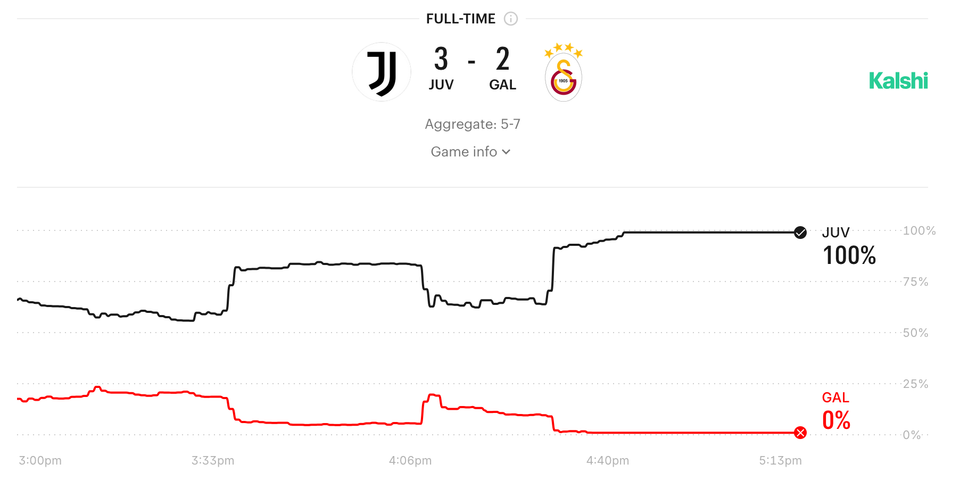

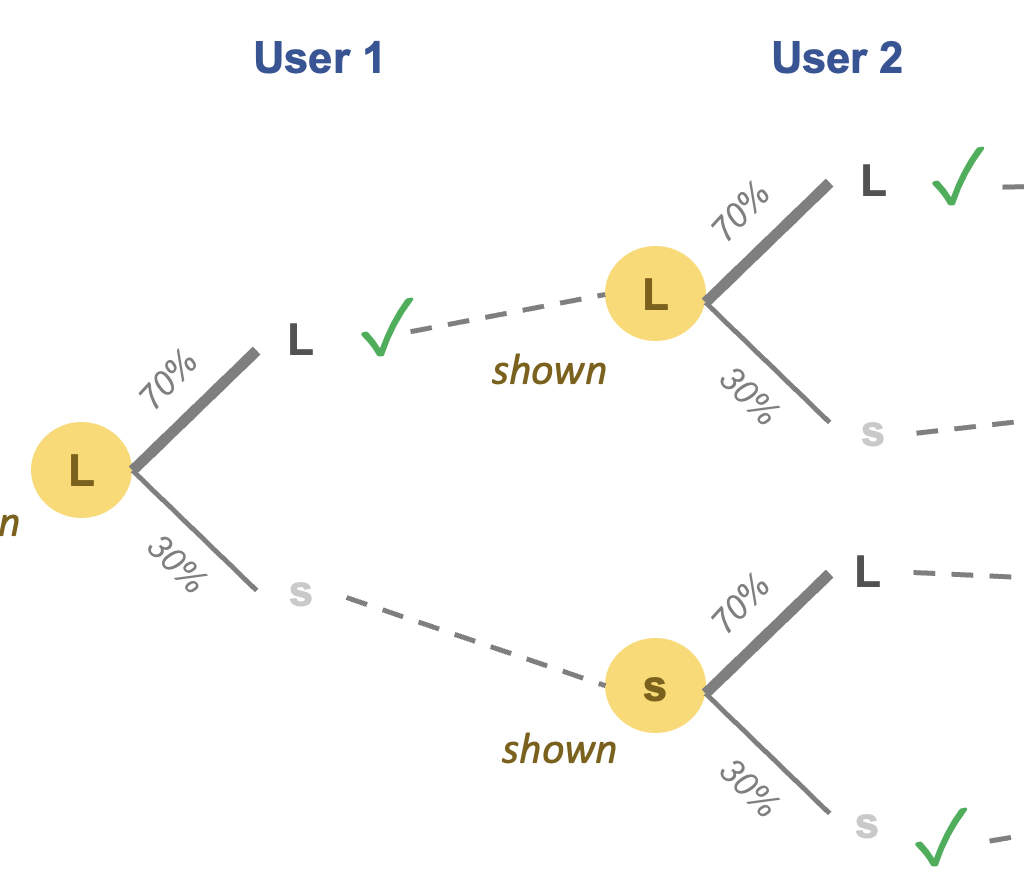

For the data nerds, this admission raises grave concerns about data collection. Imagine wanting to collect prices to estimate inflation. One method is to send people into stores to jot down prices. The data correspond to shelf prices. We now know that in dollar stores, the shelf prices may be much lower than the actual prices paid by consumers. So, the collected data are inaccurate.

Reading between the lines, we learn from the Guardian article that government bean-counters know about this issue. This is why they conduct inspections that have uncovered these price discrepancies.

The red-faced publicists for these stores had more to say:

[the Dollar General's] store teams “are empowered to correct the matter on the spot.”

This statement contradicts the other claim. If we believed the industry insiders cited above, the correct prices are the register prices, so there is nothing to "correct." By "correcting the matter," they must mean charging customers the shelf prices instead of the register prices. So, they "correct" the matter by charging the incorrect prices.

Is this a Freudian slip? Did they admit that the shelf prices are real, and they overcharge unsuspecting customers? If and when this bait-and-switch scheme is noticed, they will do the right thing.

The consumer advocates are equally confused. Since they use the term "overcharges," they must believe that the shelf prices are correct while the register prices are incorrect. If that is the case, then they can't accept that the cause of these "overcharges" is how the stores don't have the staff to update the shelf prices! But they swallowed that whole.