Story-first governing

Pay for performance, story-firsters, and trust in statistics

In the last decade, "data story-telling" first became a thing, then came the backlash. Some of my colleagues complain that data story-telling becomes more about stories than data. In other words, it morphs into what I've been calling the "story-first" mentality towards data. The story-first people decides on a story, then finds the data to support it. That's the opposite of "data-first". The world is over-run by story-firsters.

The current U.S. government is run by story-firsters. Maybe we shouldn't single them out. It seems like the U.S. government over the last decades have increasingly become more story-first. The most recent actions announced by the President are the most extreme yet.

First, he fired the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (link), the federal agency that collects and publishes various key official statistics, including the widely-disseminated inflation and unemployment rates. The gravest thing about this firing is the stated reason: the unproven accusation that she "manipulated" the data in order to make the current administration look bad.

With such reasoning, the next BLS head has to be someone who will publish only data that please the administration! Otherwise, his/her head is next on the chopping block.

(The story-firsters will say: since this administration's policies are self-evidently beneficial to the U.S. economy, any data not showing this result are flawed, and thus, the BLS head is incompetent! Or think of it this way - the firing is based on someone knowing what the "right" numbers are, and how do they know those?)

***

Second, the President announced his wishlist for "reforms" to the U.S. Census, in so doing disclosing that he has little other than surface knowledge about a census.

His biggest want is to stop counting "illegals". Every time someone wants to stop counting something, you know they have unpure intentions, because for story-firsters, no fate is worse than having to face inconvenient data. (By contrast, for data-firsters, the worst fate is to have no data.)

The entire problem of illegal immigration goes away when there is no data measuring it. Similarly, if the government don't keep statistics on crime, we can be told there is no crime.

Here too, the story-firsters have gradually gained ground. Chapter 6 of Numbersense (link) covers details of how the U.S. government computes the unemployment rate. Since the time of Clinton, more and more citizens have entered the rank of the uncounted: they can neither be employed or unemployed, according to the BLS. Nevertheless, none of these dropouts have jobs, they are in fact unemployed (in the everyday sense), so by removing them from both the numerator and the denominator, the unemployment rate improves. It looks better, but it's not because those uncounted people found jobs.

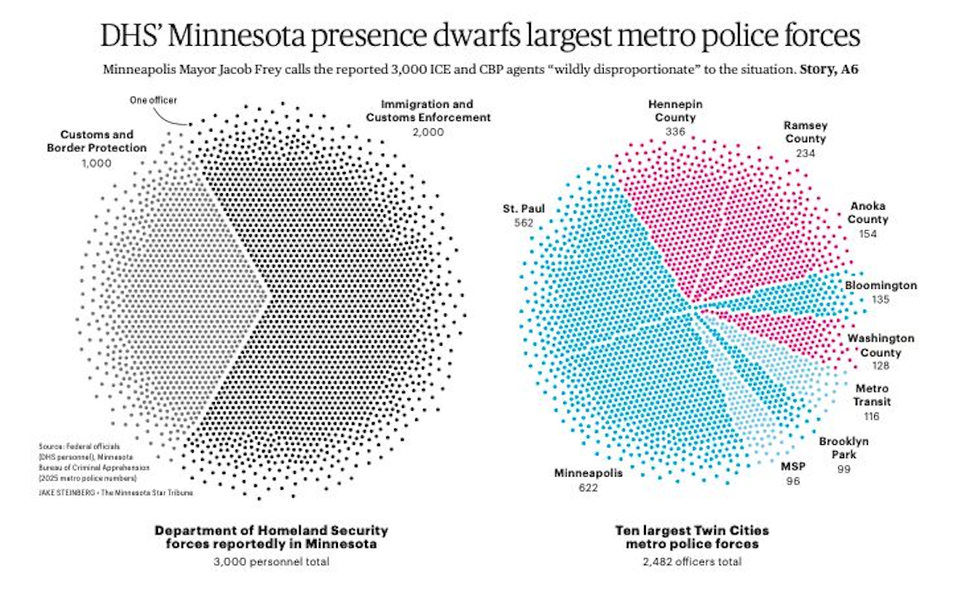

Not counting illegals means we can't size the problem. We therefore can't properly allocate resources to deal with it, including hiring enough ICE agents to snatch people off the streets, if that is your desired policy.

***

There may also be specific metrics that the current U.S. government wants to modify. Any change to a long-running instrument, whether it's altering underlying populations being measured, or changing specificiations, wreaks serious long-term damage. I discussed this issue in Chapter 2 of Numbersense (link), as it relates to the movement to replace BMI as the obesity metric.

An immediate casualty is historical comparison. The power of the Census comes from its history. Because we are measuring the same thing using the same method for a long time, we can describe trends, and anomalies. A sudden shift in the definition of a metrics literally and figuratively breaks the time series, effectively devaluing the currency of all prior work.

The inside joke is: the new metric is certainly not unbiased, nor above accusation of manipulation, because all metrics are built on top of assumptions, and those who disagree with the assumptions have grounds for bias complaints. It's like dropping everything you own to buy the new house only to discover, after you move in, that while the roof doesn't leak like the old house, the new house is infested with ants.

***

The reason for the surge of the story-firsters is covered in Chapter 2 of my book Numbersense (link) : the perversity of measurement.

Statistics are great at reflecting the health of something, such as public health, public security, educational achievement, and the economy. It is then tempting to link statistics to performance. This is usually labeled pay-for-performance, and in some quarters, treated as an axiom, something so eminently reasonable that its adoption is beyond skepticism.

Anyone who has experienced pay-for-performance knows the issue: there are many ways to "manipulate" the statistics without making real change. In Chapter 1 of Numbers Rule Your World (link), I reported an bottomless pit of methods used by enterprising university administrators to dress up their numbers, leading to better school rankings, without changing the quality of education (and in the worst cases, probably causing a drop in quality).

The "value-added" movement in education is a poster child for the perversion of measurement. When the salaries and bonuses of teachers and administrators are tied to standardized testing results, there are strong incentives to cheat. These policies are highly effective at spreading the cheating culture from students to staff.

Machines cheat too. If machines are told to maximize the number of clicks on a display ad, they learn to push a popup that interferes with what users are trying to do, thus generating many unintended clicks. The click metric dutifully reports these "fake" clicks as if they are real. Some humans notice this trickery, and seek to end it by requiring the user to remain on the ad for at least three seconds. The optimizing machines respond by withholding the "skip" button on the popup for three seconds.

...

Now, over the years, the Federal Reserve has drifted toward a "pay for performance" posture. Since the 1990s, when Alan Greenspan was Chair, the "dual mandate" of employment and stable prices is being managed by "targets". In recent years, the inflation target of 2% has been repeatedly mentioned.

The markets then interpret deviations from those targets as bad news. Lately, the administrations view stock prices as a barometer of their economic policies. The Fed is doing a lousy job, we are told, because inflation is higher than 2%, or that the market indices are reacting badly to the latest figures. And now, the President is saying the data collectors are failing when the statistics don't meet his expectations. In addition to firing the BLS head, he has been agitating to remove the Fed Chair.

I said earlier it's not just this administration. Once the "pay for performance" posture is adopted, the statistics are not just passive observers but active participants. The story-first instinct then rises to the top, encouraged by these incentives. It's a matter of time before the economic indicators point in an undesirable direction (if they never do, they aren't good metrics), and that's when the numbers get warped out of reality. It doesn't have to be blatant cheating. One can always come up with reasonable arguments to support changing assumptions or definitions. Somehow, these changes would always move the statistics in the favored direction!