When will they "personalize" pricing?

A Consumer Reports study reviews how Instacart manipulates prices of groceries

One of the oft-cited benefits of Web or mobile technology is "personalizing" the user experience. This concept starts with little conveniences such as remembering your log-in user name (via cookies). The most obvious tool of personalization is probably recommendation engines, made famous by Netflix. When a service is personalized, different users expect to encounter different experiences.

Consumers don't welcome all personalization modes. A recent survey by Consumer Reports found that 7 out of 10 respondents reject personalized pricing for groceries (link). Something about paying different prices for the same can of tomatoes offend our sensibilities. Nevertheless, it's obvious that businesses will make more money if they are able to charge more for customers able or willing to pay more; and it's equally obvious that Web and mobile tools of personalization can be extended to pricing decisions. So, it's a matter of when, not if, that we will be charged different prices from our friends for the same things.

Huge props to Consumer Reports for conducting a rigorous study that confirms something many of us already suspect is happening: personalized pricing (link).

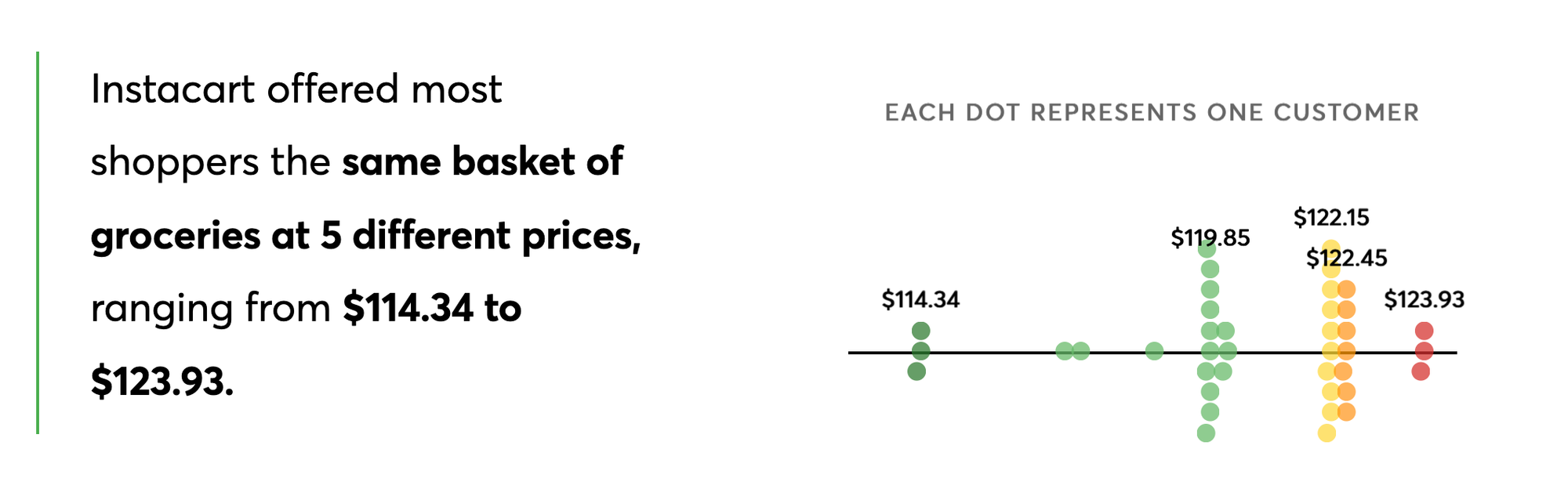

The CR study focused on Instacart, a popular shopping concierge service, by which the company dispatches shopping assistants to pick groceries from brick-and-mortar stores and deliver them to customers. Consumer Reports found that the Instacart website shows many different prices to different customers for the same item ordering from the same stores, with the maximum price sometimes as much as 20 percent higher.

Today, those customers who paid $123.93 are likely to presume that everyone is being charged the same price - that's the norm when they shop in brick-and-mortar stores with posted price tags. We're assuming they know how much they're paying. But, as described in Chapter 7 (on inflation statistics) of Numbersense (link), many American supermarket customers have no clue how much items they placed in their shopping carts cost. (I cited this research by marketing professors.)

Furthermore, there is not much a skeptical online shopper can do to learn if the store charges everyone the same prices. It's a bit easier to collect posted prices at physical stores for comparison with the online prices, but still too much a hassle for most shoppers.

Thus, online retailers have an incentive to personalize pricing because they can find more revenues from unsuspecting customers.

This is why the Consumer Reports study is so valuable.

How then did CR get around the data challenge? They recruited hundreds of people, arranging simultaneous Instacart shopping sessions for the same retailers, during which everyone placed the same basket of groceries into their shopping carts. Then, they recorded the prices. The variations in prices were visualized in the type of dot plots shown above.

The CR team seemed to be of two minds about whether Instacart is really doing "personalized" pricing. They call it "algorithmic pricing experiments."

This coinage merges two distinct concepts: algorithmic pricing, and pricing experiments. Algorithmic pricing is what I call "personalized pricing": the price differentiation is most commonly achieved by deploying an algorithm that computes each item's price while the shopper is browsing the site or using the shopping app. The goal of such an algorithm is to maximize the store's revenues.

A pricing experiment is another species. The retailer might set up five treatment "cells," say, the base price, and four variations (±5%, ±10%). Every time an item's price is required during a shopping session, a virtual die is thrown to pick one of those five price levels. Thus, those shoppers facing steeper-than-normal prices are just "unlucky." This is how Instacart staff explained the CR observations.

Normally, a pricing experiment does not use a pricing algorithm because an experiment should be designed like a clinical trial requiring random assignment of treatments (i.e. prices). Therefore, I don't use the term "algorithmic pricing experiment".

If I say "algorithmic pricing experiment," I mean something else. This test would also appear like a clinical trial, in which the treatment group comprises shoppers subjected to a pricing algorithm, and the control group contains shoppers being shown the standard, non-personalized prices. The treatment group itself would split into multiple cells with different pricing (analogous to testing dosages of medicine). The control group is included in order to measure the business-as-usual state.

Whether Instacart is running experiments or personalized pricing, an outside observer should find price variability. How then can we tell one from the other?

First, look at how widespread the price variations are. Typically, experiments affect a subset of shoppers, especially for a website with millions of customers while an algorithm represents a pricing strategy applied to all.

Second, look at how sticky the price variations are. Experiments are run to answer strategic questions, after which a strategic decision is made whether to "roll out" a change to all customers. The alternate prices are not supposed to last.

Third, look at the average prices. In my design, randomization occurs at the item level, therefore if we compute the average price differential (0%, ±5%, ±10%) across all purchases by customer over a time window, those averages should be roughly zero (if the number of items is not too few).

In the case of a personalized pricing algorithm, which sets prices to match a customer's ability or willingness to pay, we should see some customers with elevated prices, and others with deflated prices. It's hard to imagine that the average prices stay close to zero for most shoppers.

The rub is that external observers have almost nothing to work with.

In order to assess how widespread the price variations are, the study would have to recruit all subtypes of customers. To measure how longlasting the price differentials are, the study must be repeated regularly. Without access to transaction databases, outsiders can't gauge average prices by customer.

The evidence collected by Consumer Reports is very important; it's hard to ask for more. The study suggests to me that personalized pricing will become widespread within a few years, whether we like it or not.