Say Jon without the h in Chinese

Unraveling the Chinese name puzzle

When you speak to any of the so-called "smart" devices, they can hear you, and perform tasks as you request them. One of the key components of such an application is voice-to-text software. There are many nuances that trip up such software. One puzzle is homophones: since John and Jon are pronounced the same, how can the "smart" device decide which one was spoken?

Humans encounter the same problem. We make the intention clear by saying "John with the h" or "Jon without the h". How does this issue arise with Chinese names?

My friend Ray V. sent me to a nice data visualization project by Liuhuaying Yang tackling this tricky subject.

The situation with Chinese names is even more complex. Chinese names are made up of ordered characters (typically one, possibly two, characters for the surname, and typically one or two, possibly three, characters for the "given name"). The surname is written before the given name.

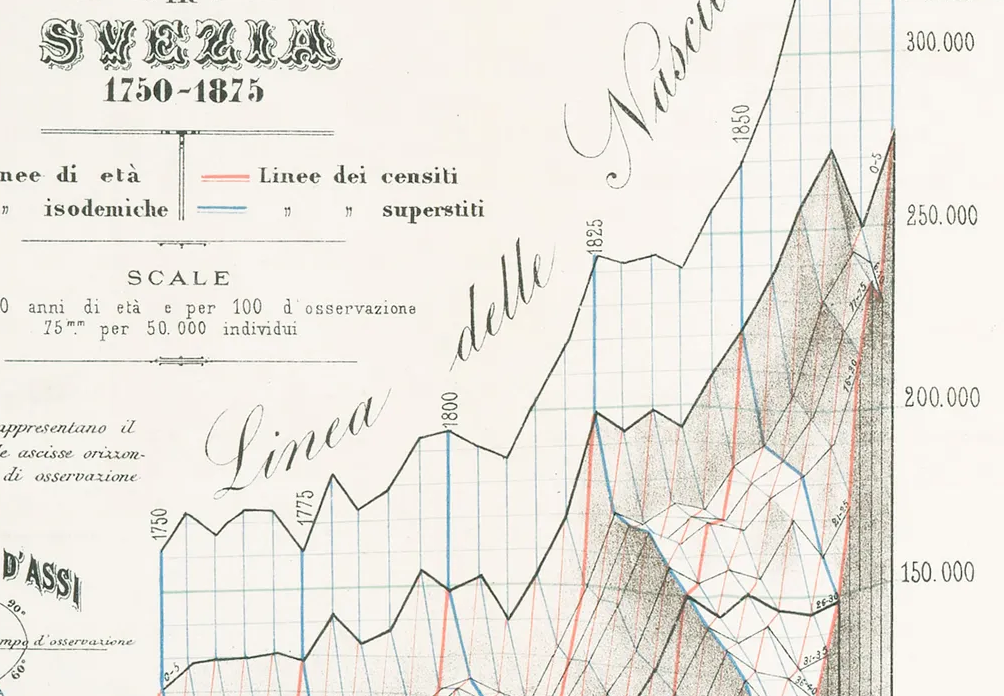

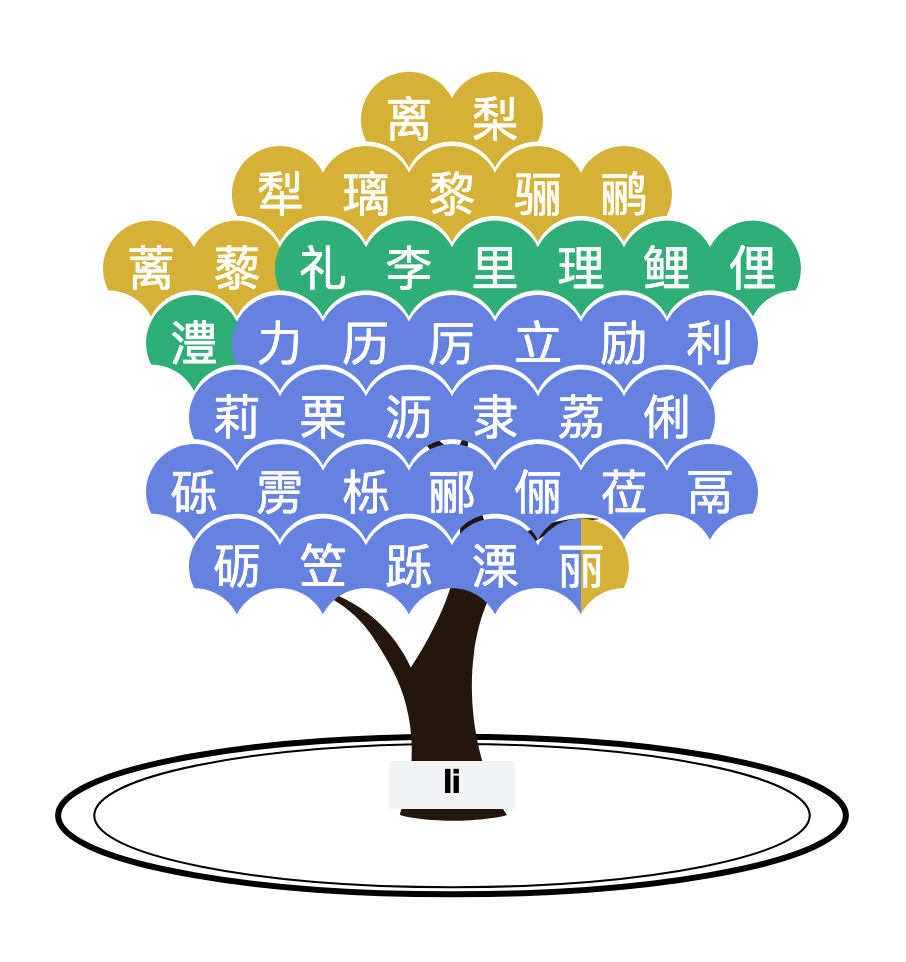

Each character is a single syllable. Homophones are numerous. The designer illustrates this as a tree:

This "li" tree contains forty "fruits," each being a Chinese character sharing the same sound. If all one has is "Li," it could be any of these characters (of course, some are more likely than others.) Thus, Li has to augment "li" by saying something like "the 'li' as used in pear." Jon without the h.

The situation is a bit better if the name is spoken out loud, because the "tone" is heard. Mandarin Chinese uses four tones, indicated by the color of the fruit in the tree above. Only three tones appear there, so apparently the first tone of "li" (shown in pink) is rarely used in Chinese names. In written text, the tone indicator is usually dropped, making it much harder to figure out which of these "li"s is the right one.

The canopy of the tree casts a shadow on the ground, the size of which encodes the difficulty of the puzzle. According to their statistics, the 40 "li"s show up in given names with a popularity of 38 per thousand people. If you look more closely, there are two shadows. The thicker shadow is related to surname usage while the thinner one, usage in given names. One of the "li"s is one of the top five surnames in China, and so the thicker shadow is the outer one (76 per thousand).

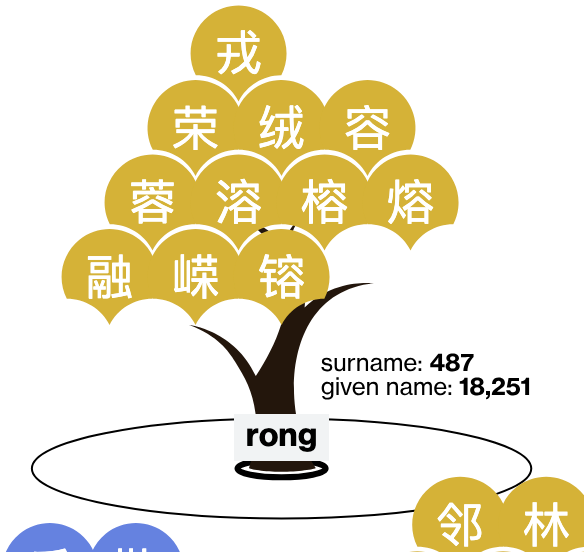

The writeup neglected to explain the two shadow rings. So, let's find one that has the opposite characteristic as "li" for comparison.

"Rong" is rarely a surname so the thicker shadow is right at the base of the trunk while the thinner shadow related to given names is more visible. Interestingly, only one of the four tones appears in this "rong" tree.

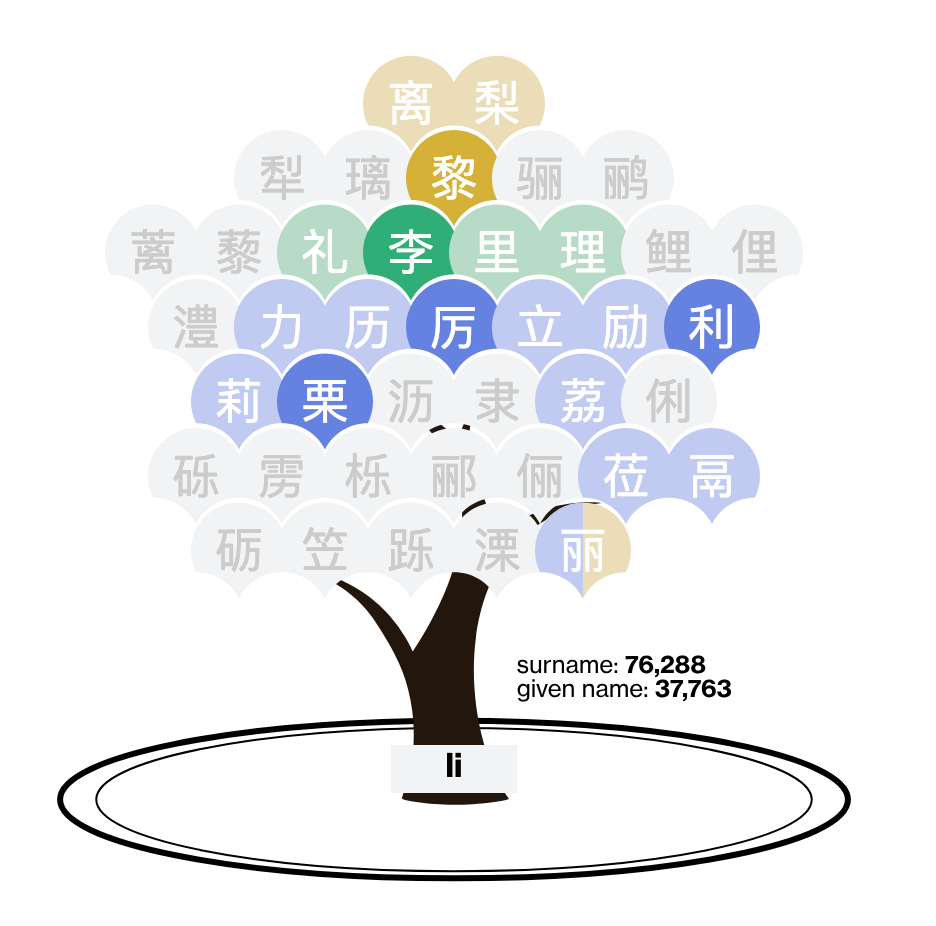

Returning to the "li" tree, let's analyze "Li" as a surname.

The character in green is the second most common surname in China, but there are about a dozen other characters that can be someone's family name. Unsurprisingly, many of these characters only show up in given names. Because they are using the tint of the color to show relative popularity, we don't really know the drop in popularity relative to the green character (it's a huge drop-off).

The value of this data visualization project is in structuring and presenting the data in a way that engages readers. This is a project that keeps readers focused on the trees, while losing themselves inside the forest, hopefully at will.

Enter the forest of Chinese names here.